A Tale of Two Asias

May 15, 2023

It was a time of great wealth and poverty, of wisdom and foolishness, of belief and incredulity. A season of light and a season of darkness — where hope and despair existed side by side. This is the story of Asia today, where rapid economic growth has vastly transformed the region in the past few decades, but left millions behind in the shadows of progress. This is the very paradox of the modern Asian economy, where the best of times and the worst of times exist side by side, in a spring of light and a winter of darkness. These inequities in East Asia have led to the rise of coffin homes, which stand as a stark symbol of poverty and neglect.

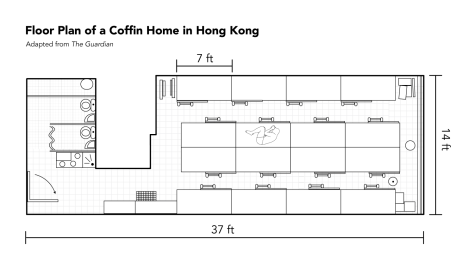

A mere 15-minute walk away from Hong Kong’s most opulent shopping center, 30 residents live individually in 60-centimeter-wide, 2-meter-long bunk beds separated by sliding doors—otherwise known as “coffins.” Devoid of sunlight and fresh air, these coffin homes house some of the poorest people in one of Asia’s richest cities.

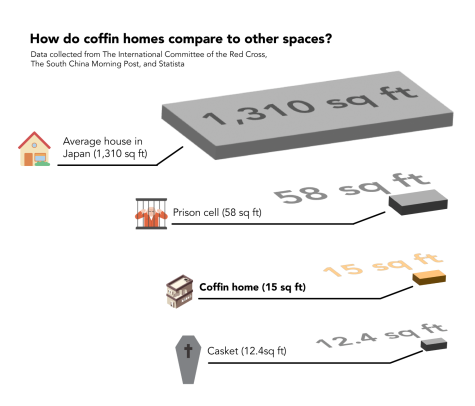

Unlike their namesakes, these homes do not provide a dignified repose for the living, let alone the dead. Instead, as Hong Kong resident Audrey Kwok (16) describes, the accommodations are “often just big enough for an adult to lie down and sit up.” Often stacked on top of each other, these tiny, $200-a-month coffin homes are symbolic of the nation’s growing housing crisis, which has only worsened in recent years due to COVID-19.

While these steel cages were intended to be a provisional refuge for the homeless and unemployed, many reside within their coffin-like quarters until their real deaths.

Kwok explains that “Despite coffin homes being presented as a ‘temporary’ living space for those waiting for public housing, people find themselves living in these houses for years on end due to high demand.” She adds, “There are often bed bugs, mold, no natural light, and an overwhelming abundance of noise, ”painting a grim picture of the unbearable living conditions that many endure in these coffin homes.

Basic necessities such as bathrooms and showers are located in a communal space near the beds, shared by upwards of 20 people. Though these spaces are often sought by young professionals that spend most of their time outside, they also house ex-convicts and drug abusers as well as children. Together, they make up the 200,000 people in Hong Kong living in subdivided apartments—18% of which are younger than 15 years old.

But these dire living conditions in Hong Kong are not an Asian exception: apartments in Tokyo’s Shibuya district tell a similar story. The demand for what are colloquially known as geki-sema, or extremely cramped share houses, has risen as the city faces rising costs of living and increasing construction costs. (The growing trend of urban migration doesn’t help, either.) Variants of these geki-sema also exist in South Korea (‘goshitels’) and China (‘capsule homes’), and they serve the same function as Hong Kong’s infamous coffin homes.

Sarvesh Prahbu, who currently works for the Korean Cultural Center in India and has previously lived in South Korea, explains that the horror of these homes “leaves a deep psychological scar in the minds of children who grow up” there, with many reporting self-esteem issues later in life. “The prevalence of crime, thievery, and lawlessness leads them to disregard and lack trust in the system,” he says.

But how did we get here? These East Asian cities have long been hailed as glittering, gilded symbols of economic growth and industrial development since the 1950s, with Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Seoul each having developed into international financial powerhouses in the post-war era.

But it is this economic growth that is, in part, to blame for the housing crisis. Alongside an economic boom throughout the 70s and 80s, Asia experienced an urbanization rate unprecedented in history, overwhelming cities with millions of migrants.

While East Asia’s meteoric economic growth was fueled largely by an increase in urban cities, demand for housing grew rapidly during the same timeframe, with little land and supply to accommodate such developments. By 1970, over 70% of residents in Japan lived in urban centers: a 40% increase from the preceding decade.

Enter the 21st century, and housing prices have skyrocketed like never before. Average house prices in South Korea and Hong Kong are now 19 times and 21 times that of the median household income respectively. Apartment prices in Japan recently reached a 30-year-high. These figures surpass even the most expensive cities in the West, with the cost of living in San Jose, California and Greater London standing at 12.8 and 8 times that of the median income.

Arising out of the high demand for affordable and cheap housing, coffin homes emerged in the 1950s as a flimsy bandage to the housing crisis in Hong Kong, and at that time mostly housed new migrants from China. Since then, variants of coffin home have sprung up across Asia’s metropolitan centers, from Tokyo’s geki-semas to South Korea’s ghoshitels.

But without awareness among both the public and the government, it becomes a challenge to acknowledge and address the magnitude of the issue.

Buried in the outskirts of quickly gentrifying cities such as Sham Shui Po and Mong Kok, to many, these coffin homes are out of sight and out of mind. Hong Kong resident Kwok explains, “Instead of the houses being a problem we try to solve, it seems like everyone has become desensitized to them.” With the housing crisis being a prevalent issue for decades in Hong Kong, it “seems normal” to have less-than-ideal living conditions. Its distance from most people’s daily lives has led to a sense of apathy and disengagement.

Sarvesh from the Korean Cultural Center of India agrees. “We turn a blind eye but it is an open secret,” he says, noting that media attention on these living conditions is “rare.” Unsurprisingly, grimy slums and ghettos often fall short of favorable viewer ratings.

That being said, governments have begun to take notice of the issue that has persisted for decades. Hong Kong implemented a vacancy tax on new homes and lowered public housing prices in 2018. Similarly, South Korean President Moon and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transportation (MOLIT) adopted a two-pronged policy of curbing speculative demand and fostering “real demand” for housing.

Whether or not these legislative actions have made a dent in mending Asia’s housing crisis is yet to be seen.

Amidst the towering skyscrapers and bustling streets of East Asia’s glittering metropolises, there are also the cramped and often squalid conditions of coffin homes, where fumes of meth and mold embalm the urban poor—a poignant reminder of the contradictions that exist within this rapidly transforming region. It is a tale of two realities existing side by side: one in which wealth and privilege thrive; another where poverty and inequality persist. Our economic structures are built to produce and perpetuate an egregious humanitarian tragedy until we work to rectify this systemic imbalance.

Rising inequality should never be a foregone conclusion in a 21st-century economy. By entombing society’s most impoverished in dehumanizing coffin homes, we accept economic inequality as a fait accompli.

Hana • Jun 1, 2023 at 8:52 AM

I found this article fascinating. Extreme housing prices causing people to live in suboptimal places are definitely a problem. This article shed light on the imbalance of housing in Asia. Thank you for this deep dive into “coffins”.