A Life in Print: An Interview with Motoko Rich

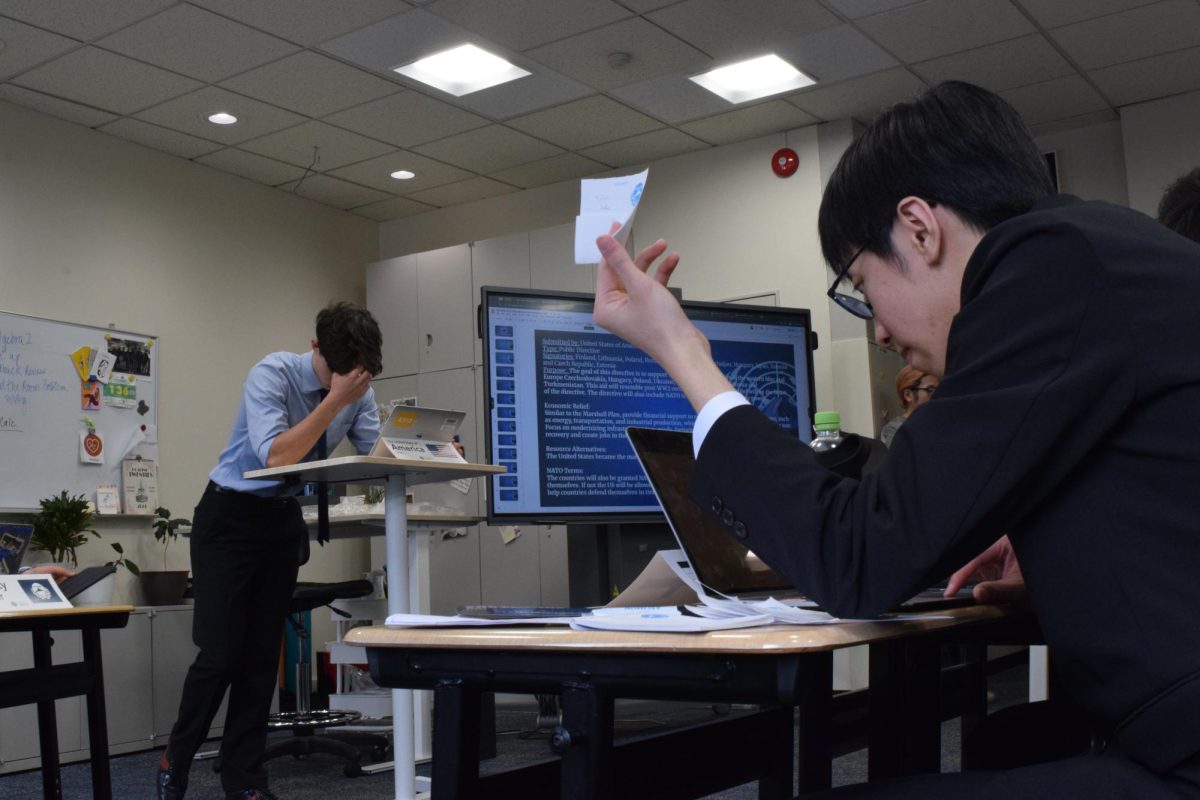

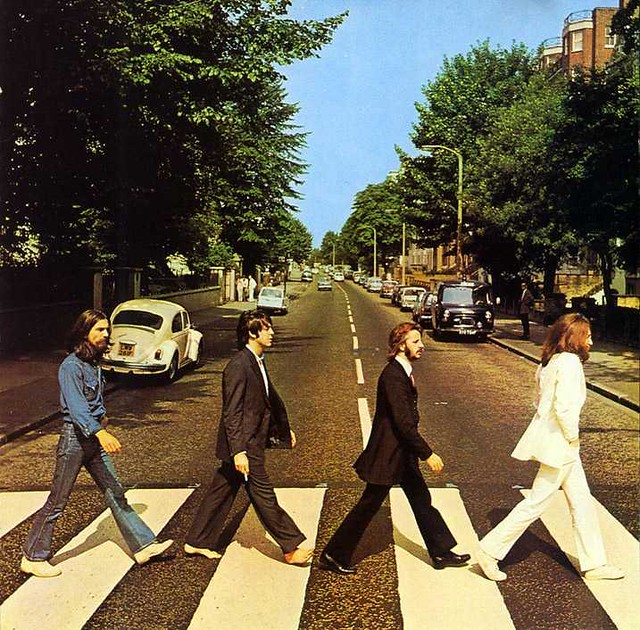

Photo by Dohyun Kim

June 7, 2019

A few weeks ago, Dohyun Kim and I were lucky enough to interview Motoko Rich, the Tokyo bureau chief for the New York Times; she began working for the Times in 2003. She attended ASIJ from second to fourth grade.

Ms. Rich initially didn’t want to become a journalist, explaining that “when I was your age I actually thought I wanted to be a novelist.” When she arrived at Yale for college, however, she joined a magazine on campus and “sort of just fell in love with the staff.” Even when she approached different occupations, she always felt herself drifting back towards journalism: “I love it to this day and I’ve been doing it since I was 24 years old and it’s such a great career.”

“It’s the best job in the world. I just love it so much because you have so much autonomy,” Ms. Rich says. Driven by her own interests and gaining the editors’ trust, she can dive into the topic of her choice and follow her natural curiosity. She has “seen so many places and met so many people that [she] wouldn’t have on [her] own,” including visiting Hanoi during the recent Trump-Kim summit and discussing film with Hirokazu Kore-eda, the director of Shoplifters. Plus, she does what she loves—write. With this freedom, however, also comes the time pressure to report. She says that her “life is never [her] own” and that she’s had to wake up in the middle of the night to report on the latest developments. She has to get information as fast as she can, revise rapidly, and handle demanding deadlines.

We asked Ms. Rich about sensationalistic articles, fake news, and inaccuracy in the media that stems from the immense pressure to produce content. In the case of the New York Times, she asserts that the “bottom line is that we take very seriously accuracy.” For example, during the Boston Marathon attack in 2013, information on potential suspects were circulating. While some papers ran with it, the NYT could not verify this information so they did not publish names; it turned out that those names were inaccurate. She states that “there’s nothing worse than getting something wrong,” and even that that “if [she] spelled someone’s name wrong, [she] lose[s] sleep over it.” While anyone can put information out on Facebook and Twitter, she points out, when people subscribe to reputable news sources—NYT and beyond—they are paying for vetted, fact-checked content.

When we asked about her thoughts surrounding the current White House and the President’s attacks on the free press and the NYT, she replied that she firmly believes that the fundamental mission to pursue truth applies to any president of any party. However, when President Trump uses phrases such as the press being the “enemy of the people,” she believes that it is incredibly damaging as this is rhetoric used by totalitarian regimes. The NYT’s publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, met with President Trump to respectfully stress the importance of the free press. She feels “very proud to work for [the NYT] … and very relieved and very protected to have him out there like that.”

Ms. Rich recognizes that there is an extremely polarized political atmosphere right now, and hopes to avoid becoming a part of that. Even the mere appearance of a conflict of interest is a problem; she is not allowed to donate to political campaigns or protest in political rallies. The NYT takes its responsibility seriously—the organization even has an employee whose sole job is to deal with ethical issues.

Despite its difficulties, being a journalist is rewarding. Ms. Rich has had many favorite pieces over the timespan of her career and feels “really, really lucky because [she’s] covered so many different things.” At her first job at the Financial Times, she was tasked to cover topics such as chemicals and currency—subjects she was initially not interested in. However, this resulted in an immense learning opportunity: “One of the great things about being a journalist is that you find out that actually everything is interesting; if you get to know it a little bit, you learn more about it, you start asking questions, you talk to the people who are passionate about whatever you’re writing about, then you find out that everything in life is actually quite interesting, which is a really good lesson.” More recently, she wrote a piece about working mothers in Japan for which she had the “fascinating” opportunity to interview “normal women.”

On the other hand, Ms. Rich says that she has faced many professional challenges. In particular, she has found that collecting information in Japan is more difficult than in the Western world as there are institutions set up — such as Kisha Clubs (記者クラブ) — that make reporting opportunities exclusive. She grew up in a different culture, where the press is the ultimate watchdog of government and business: “Our job is to find the things that people are trying to hide from everybody else,” she asserts.

She has sometimes been frustrated reporting in Japan, recalling some interviews in which the interviewee requested to see all the questions beforehand and wouldn’t answer any others. This “goes against every instinct I have as an American-trained journalist,” she explains.

Ms. Rich has an unwavering moral compass and conviction to pursue the truth, question others, and fulfill her role as a watchdog for society. Her frankness, honesty, and heartfelt passion were inspiring, and I walked away with a renewed sense of admiration for journalists who seem to do the impossible every single day.