Louise Glück and The Nobel Prize

January 22, 2021

There are those few people in this world who can articulate emotions and a situation so well it’s frightening. Louise Glück—whose name rhymes with “click” and not “cluck”—is one of those people. Glück is a recipient of many awards for her profound poetry, such as the Pulitzer and Bollingen Prizes, the MIT Anniversary Medal, the Wallace Stevens Award, and, most recently, the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature.

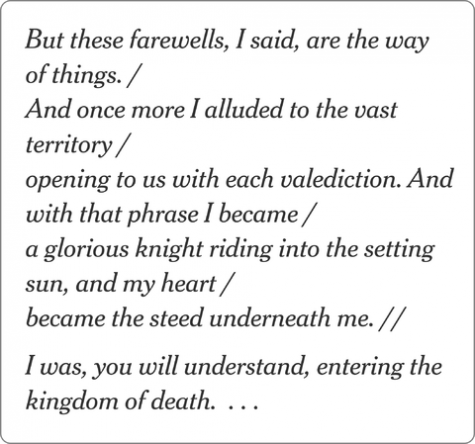

Glück was born in New York and grew up on Long Island. She attended Sarah Lawerence College and Columbia University and is now a writer-in-residence at Yale University. She has published twelve books of poetry, most of which have been honored and awarded. Praised as one of the best American contemporary poets, her work deals with family relationships, loneliness, vulnerability, trauma, marriage, divorce, and death.

Amongst the 117 people who have received the Nobel Prize for literature, Glück was the 16th woman to win the award. The Swedish Academy recognized her for “her unmistakable poetic voice, that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

But there was also criticism that came when the Nobel was announced on October 8, 2020. Some critics said that Glück was too obvious or too safe a choice. Nevertheless, the criticism is quite minor.

In her earlier days, Glück seemed to be a peculiar child. In her Nobel Lecture, she reminisces on times as a five year-old child, making fictitious competitions that she believed would indicate what poem is the greatest in the world. The “competition” came down to Blake’s “The Little Black Boy”and Stephen Foster’s “Swanee River.” Glück would pace around her grandmother’s house, reciting the two poems. “Blake was speaking to me through the little black boy; he was the hidden origin of that voice,” she explains. “He could not be seen, just as the little black boy was not seen, or was seen inaccurately, by the unperceptive and disdainful white boy.”

Poetry has always been Glück’s first language. It’s the way she communicates with others who may live different lives. In all her poems, her percipience is combined with honesty and sharp wit. Many go as far as to compare her to Emily Dickinson, which of course she finds flattering.

But once, when asked about her popularity in a 2009 interview with the American Poet magazine, Glück said she thought, “Oh great, I’m going to turn out to be Longfellow: somebody easy to understand, easy to like, the kind of diluted experience available to many. And I don’t want to be Longfellow.”

Glück’s discomfort with popularity is the notion that all great poets want to be left alone. Disturb their solitude, and they will feel uneasy. After all, they got into the career to create poems only, not to be recognized by millions or have paparazzi follow them—which was the case on the day she won the Nobel.

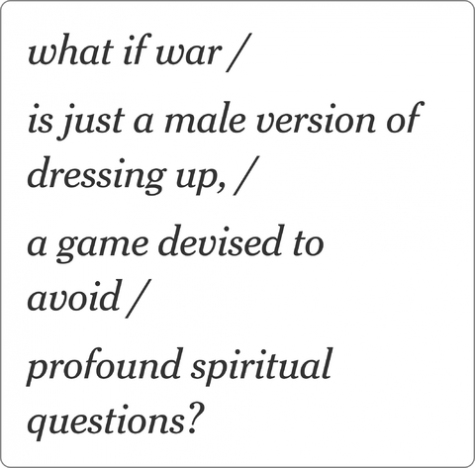

Louise Glück’s poetry welcomes the reader into her perception of the world. Her most notable work includes “The Wild Iris,” “First Memory,” “A Fantasy,” “Meadowlands,” and “Parable of the Hostages,” the latter a poem set during the Trojan War. In this poem, two Greeks are sitting on the beach “wondering what to do when the war ends.” It is a satirical poem, as the Greeks think to themselves how much they don’t want to go back to their relatively mundane lives after fighting in the excitement of the Trojan War.