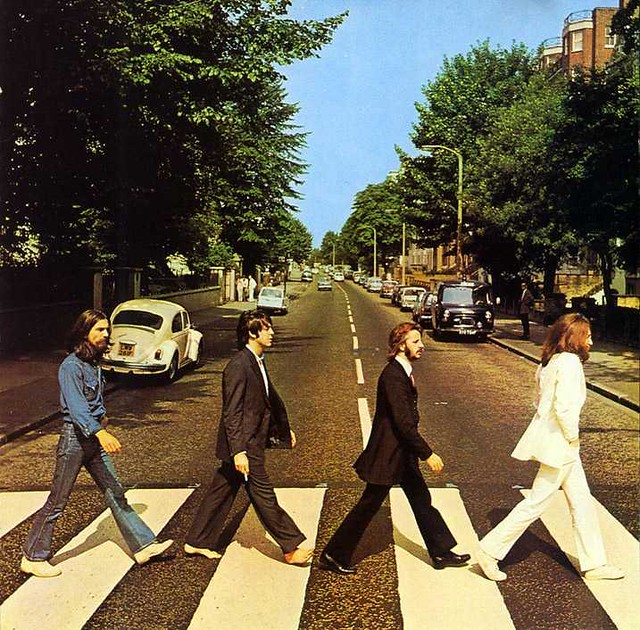

A quick Google search on who is the biggest band in music history will immediately present you with the Beatles. Their “Abbey Road” album cover appears as an easter egg in countless movies, “Here Comes the Sun” plays at least once in every department store, and nearly five decades after their breakup, the Fab Four are still cited as the inspiration for many modern artists. Yet, in the modern day, their legacy has become subject to criticism, with more music fans calling the band “overrated.” This comment, however, is often stated in disregard to how the Beatles progressed classic rock and their undeniable influence in growing the many sub-branches of the genre. Not only did the Beatles spend a total of 132 weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard 200, but they also paved the way for numerous musical genres, showcasing a level of versatility unrivaled by other bands in a time of conformity.

Early Beatles

Originally a simple rockabilly band, the Beatles —John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Pete Best (who would be replaced by Ringo Starr just before their big break)— dressed in teddy boy attire and played classic Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley hits. Their potential was noticed by their future manager, Brian Epstein, in a performance at the Cavern Club in Liverpool. Epstein introduced them to producer George Martin, who signed the group. In the span of three years, the Beatles went from playing in local pubs in Liverpool to touring sold-out stadiums in the US.

Fans squealed and fainted just at the sight of the four boys. The term “Beatlemania” is used to describe the intense hysteria that the Beatles were met with. It is easy to question why the Beatles received so much praise for simply writing songs about holding hands and other “silly” love lyrics, but it is necessary to consider the time that the Beatles peaked: post-World War II.

Ozzy Osbourne, former singer of heavy metal band Black Sabbath, commented on his love for the Beatles, stating, “You don’t forget, we came out of World War II and the whole thing. We had strict rules to live by. And it was that they broke the f***ng doors down for so many people, and they gave freedom to the world.”

All humans are entitled to love; love is a basic human necessity that everyone has felt in one form or another. In a dark world suffering the loss of 35 to 60 million lives from World War II, little love songs brought light. Thus, it was only natural that people in the early 60s would find the Beatles so fantastic. They served as a source of lightheartedness and excitement in a world still recovering from tragedy.

Love is a timeless part of human nature. As McCartney once sang, “Some people want to fill the world with silly love songs / And what’s wrong with that?”

In what would later become a notable trait of theirs, the early Beatles were not afraid to experiment with the technical aspect of songwriting. “Ticket to Ride” of the 1965 Help! album promoted the idea that a song does not have to follow a strict, rigid structure. The outro of “Ticket to Ride” completely strays from the original melody of the verse and chorus: its tempo picks up, and Starr’s drumming almost sounds like a hard rock beat. “Ticket to Ride” indicated that the Beatles were not just following the standard song structure of other classic rock artists of the time. Instead, they were innovating their approach to songwriting.

1966 Expanding Variety

The Beatles also helped bring Indian influence into Western music. Rubber Soul, arguably the album that marked the Beatles’ change into more diverse sounds, includes the song “Norwegian Wood.” Played by Harrison, it was the first Beatles song to contain a sitar. The sitar gave the track a more rich and mystical tone, perfectly complimenting the song’s story of a girl the singer once knew and her sudden departure the day after they met. With their intense level of fame, the Beatles helped popularize the classical Indian sitar in rock music.

A year after Rubber Soul’s release, the Rolling Stones included a sitar in their 1967 album Their Satanic Majesties Request, inspired by Harrison’s sitar, but also by the Beatles’ later album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The second 1966 album, Revolver, sowed the seeds for the Sgt. Pepper album. Revolver is the stronger symbol of the turning point in the Beatles’ career. The sitar was used again — along with other Northern Indian classical instruments — in Harrison’s “Love You To,” which took even more influence from Indian classical music by incorporating classical Indian singing and song structure. Harrison imitates khyal vocal technique from Hindustani classical music and uses a drut, a Hindustani technique that finishes a song by accelerating the tempo.

However, It was not only Harrison who changed how classic rock was written. McCartney’s “Eleanor Rigby” is a haunting piece with an orchestral accompaniment that sings of loneliness in a time of upbeat energy foreshadowing the 70s. His melancholic “For No One” incorporates a French horn solo—not something often seen in rock. Lennon’s “Tomorrow Never Knows” is the hazy, dream-like sounding finish to the album that uses sped-up and reversed tapes to create a hypnotic, otherworldly setting, unlike what any other rock band had done. The Beatles still would have been a well-known classic rock band if they had continued along the likes of their earlier works, but it was Revolver that pushed the boundaries of rock and placed the group as the standard for other bands to attempt to meet.

1967: Entry into New Grounds

Revolver was the precedent for the 1967 Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and is undeniably one of the greatest rock albums of all time. Late 60s rock was when artists truly felt freedom to experiment with new concepts in contrast to the previous decade’s strict musical structure, and the Beatles pioneered this evolution. The Sgt. Pepper album’s opening track immediately greets the listener with a distorted electric guitar riff that sounds almost like an 80s guitar tone. Though it is not perfectly confined within the definition of a concept album, the album still manages to take the listener through a street of all the songs’ protagonists, earning the title as one of rock’s first concept albums. The Sgt. Pepper album inspired other bands to get creative both musically and technically.

Lyrically, the album established that songs could be about anything. Love will always remain a popular theme in music, and rightfully so, but Sgt. Pepper showed that songs could range from everyday life to fantasy-like storytelling. For instance, McCartney’s “She’s Leaving Home” tells of a teenage runaway that he had seen in the newspaper, while Lennon’s “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” sings of “a girl with kaleidoscope eyes” and “rocking horse people eating marshmallow pies.” Themes of fantasy mixed with personal experiences gave way to one of the Beatles’ most celebrated tracks, “Strawberry Fields Forever” (though it would be released as a single instead of being put on the album), in which Lennon sings cryptic but vulnerable lyrics inspired by a Salvation Army’s children home near where he lived.

Moreover, Sgt. Pepper experimented more than ever in how music was produced. Unlike the standard three-second pauses in song transitions in previous rock music, each song in Sgt. Pepper immediately starts at the end of the last song. This continuation influenced concept albums as, without a three-second pause, songs were able to feel more connected to each other. The Beatles also spent a whopping 700 hours perfecting the album as they had to carefully mitigate the consequences that came with bouncing many tracks in order to get all the sounds they wanted. In this way, Sgt. Pepper encouraged working on an album until it was the absolute best it could be instead of the common practice of booking a studio for a few days.

Additionally, the Beatles themselves dressed up as members of the Sgt. Pepper band in bright-colored marching band-like attire, inspiring other artists, like David Bowie and KISS, to take on stage personas. It is no doubt that without Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, classic rock artists would never have gained the confidence to convey their true selves and ideas and use music as a means of expression rather than commercialization.

1968’s Avant-Garde Experiment

A year after the Beatles’ second 1967 album, The Magical Mystery Tour, the most experimental Beatles album, The Beatles, was released. Commonly referred to as the White Album, it was raw and revolutionary. The four men wrote the album during a time of confusion and grief after their manager, Brian Epstein, died, resulting in a pure manifestation of creativity and intimacy. With thirty songs ranging from soft ballads, like Lennon’s “Julia,” which sings of his deceased mother, to McCartney’s cartoon-like “Wild Honey Pie,” the Beatles abandoned all that was left of their Beatlemania characters.

The Beatles and metal may sound odd in a sentence together, but McCartney’s “Helter Skelter” paved the way for heavy metal in the 70s. Aggressive and thunderous, “Helter Skelter” features a blaring guitar, distorted bass, crashing drums, and McCartney’s absolutely unrestrained vocals. Just years later, hard rock and heavy metal bands, like Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, sprung up. Capturing raw, unscathed energy into a song, the Beatles set the blueprints for metal, a genre defined by its gritty and intense tendencies.

The band also expanded their vision to include protest songs. McCartney wrote “Black Bird” as a message of hope for African American women in the 60s to overcome the struggles they faced. Lennon wrote “Revolution 1” to denounce violence in protests. Harrison wrote “Piggies,” remarking on class and corporate greed. The Beatles used their immense platform to advocate for social change. As a result, they helped establish that rock can be political, pushing both musical and cultural values.

The contrast in songs like the avant-garde music collage “Revolution 9” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” encouraged other artists to push the limits of their musical abilities, whether that be in their creativity or what messages they sent forth. For an album in the 60s, The Beatles served as the prototype for other genres like metal and encouraged artists to make their music personal and purposeful, connecting back to their roots as artists rather than celebrities.

Final Two Albums

After the tumultuous recordings of the White Album, the Beatles knew it was time to part. Finishing their career after nearly ten decades, the Beatles channeled all chemistry left in them to release two last albums: Let It Be and Abbey Road.

Let It Be was recorded before Abbey Road but released after and served as a guide back to the original Beatles’ roots. Songs like “One After 909” resemble the Beatles’ initial introduction to music through the blues.

The title track, inspired by McCartney’s deceased mother and messages of hope and determination, is one of the Beatles’ most prized recordings, resonating with all listeners, regardless of background. Its universal message of carrying on demonstrates beauty in simplicity, but its blend of an electric guitar, organ, and orchestra highlights beauty in intricacy.

Let it Be managed to produce early ’60s blues tracks that older generations would prefer but are also suited for new listeners and future generations. In doing so, the Beatles created an album that transcends time. Harrison’s “I Me Mine” is one of the most prominent examples of this feat as it transitions from intervals of a soulful waltz, more aligned to the taste of new generations, to straight rocking blues, a trend of the older generations.

Abbey Road, typically dubbed their greatest album, was absolutely groundbreaking. For the first time in their career, the Beatles made an album specifically designed for stereo, rather than their previous albums’ recordings made for mono. Whereas mono uses one audio output, stereo uses two audio outputs, allowing for more creativity in how an artist can express their song. Each song of “Abbey Road” was carefully crafted to create a favorable balance for the listener in the two audio channels.

Already casting a fierce hypnotic spell with its constantly swapping time signatures and the cycling chord progression of the guitar, Lennon’s “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” is further intensified by the stereo audio separation. The bass, rhythm guitar, and overdubs flood the left channel, while the main overdriven guitars and cymbals take over the right channel, accentuating the chaotic sensation that Lennon felt toward his new wife, Yoko Ono, whom he wrote the song about. The gradually increasing white noise toward the end of the track centers all of the listener’s attention on the overdriven guitars, creating almost a suffocating effect. When the song’s chaos abruptly ends, the listener feels a void. All of the nearly eight-minute-long buildup never reaches the climax; it merely ends. The song’s innovative quirks would inspire progressive rock, as seen in albums like Radiohead’s dystopian Ok Computer.

As the pinnacle of the Beatles’ versatility, Abbey Road explores a variety of subgenres in rock. “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “Octopus’s Garden” are upbeat, mellow pop-rock-like tracks that balance instrumental quality with whimsical and storytelling elements. Meanwhile, “Oh! Darling” is an old-fashioned love ballad, and “Because” is a progressive-rock style melody based on a reversal of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. The Beatles demonstrated that artists are not limited by the constraints of their genres. Though artists tend to gravitate toward singular styles, in the end, they still use their imagination, which has no constriction. If artists embrace their ideas no matter how obscure they are compared to their norms, they may end up expanding genres just as the Beatles did with rock.

Every Beatles member is in some way known for their creativity in their instruments, but McCartney especially shined in Abbey Road, promoting bass players to write basslines more than just root notes on the low E string. He could have played the original melody of Harrisoin’s “Something” for the bass support but instead built a bassline that weaves around Harrison’s lead. Again, in “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” his bass ferociously ascends and descends, further contributing to the chaos of the song. McCartney’s bassline evolved how the bass was played; rather than merely keeping rhythm with a few notes per measure, basses could sing and wail just as guitars could. Later decades would see more complex and entertaining basslines, like Cliff Burton’s works in Metallica and John Paul Jones’s contributions to Led Zeppelin.

Perhaps Abbey Road’s greatest accomplishment, however, is the well-renowned Abbey Road medley. Beginning with “Mean Mr. Mustard,” each song morphs into the next until the second to last song of the album, “The End.” Though not the first medley in rock history, the medley was absolutely monumental. It was composed of unfinished song snippets that seamlessly flow into each other, portraying the Beatles’ insistence on taking risks and their unmatched talent in making something so extraordinary from nothing. Transforming sheer scraps into sublime songs, the Beatles undisputedly possessed an innovative sense of ingenuity. Managing to connect a collection of songs into a continuous stream, where each song, despite style, builds off the outro of the last, is a challenging feat that the Beatles perfected, even in times of tension from the band’s fallout.

Abbey Road, the Beatles’ final studio work and ultimate message to the world, changed the course of music. Its experimental stereo, innovative instrumentals, and mesmeric medley gifted other artists, past and present, the courage to ignore conventional norms and pursue their earnest ideas. As a culmination of their full career, Abbey Road puts every trick and skill the Beatles learned on full display as proof of their lasting legacy.

In their decade-long reign, the Beatles proved their ability to resonate with all individuals —whether that be in love, societal challenges, or other human experiences— through their innovative usage of studio techniques and their pure creativity. In no way can the Beatles be considered overrated with their influence in genres like metal and subgenres like progressive rock, as well as their reminders to other artists to not forget what art is made for: not money or recognition, but to provide a sense of understanding with other human beings.