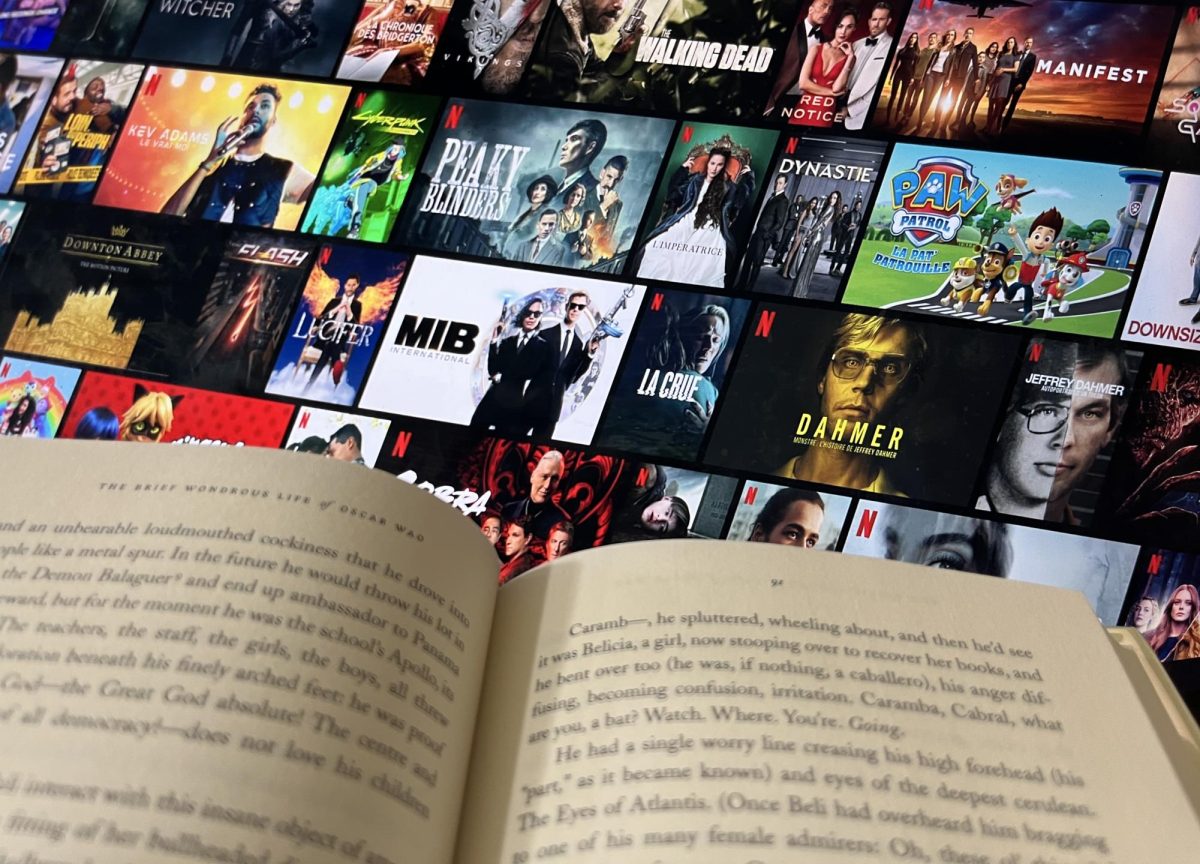

We all have favorite fictional stories. It’s not only the plot that attracts us to stories, but the characters that make or break a good tale. Movies, TV series, books, and games are all forms of media that tell us the stories of such fictional characters. If you find yourself relating to these characters, scientists now have a better idea of how this happens. Researchers found that the act of relating to a fictional character activates the same part of the brain used when a person thinks about his or herself.

According to Science Daily, a study done by Dylan Wagner, an associate professor at Ohio State University, and current postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University, Timothy Broom, scanned the brains of Game of Thrones fans using an MRI machine. They observed a part of the brain called the medial prefrontal cortex (vMPFC) which shows increased activity when people think about themselves and occasional activity when people think about others.

Wagner and Broom’s experiment was simple. While participants’ brains were being scanned, they were shown a series of names: sometimes their own name, sometimes their friends’, and other times a name of a Game of Thrones character. The names showed up above a trait such as “sad”, “compassionate”, “lonely”, or “intelligent”. They then answered “yes” or “no” to whether that trait applied to that person.

The results were as predicted when observing the vMPFC. That part of the brain was most active when the participant was evaluating themself, less when evaluating their friends, and least when evaluating the Game of Thrones characters.

However, a key finding involved participants who scored highest on “trait identification”. In a questionnaire completed as part of the study, these participants answered positively to questions regarding emotional engagement in stories.

“People who are high in trait identification not only get absorbed into a story, they also are really absorbed into a particular character,” Broom said. “They report matching the thoughts of the character, they are thinking what the character is thinking, they are feeling what the character is feeling. They are inhabiting the role of that character.”

For the participants with high trait identification, the medial prefrontal cortex was more active when they were thinking of fictional characters than others who identified less with the characters. The vMPFC was even more active when the participant thought about a character they related to and favored most.

“The findings help explain how fiction can have such a big impact on some people,”said Dylan Wagner. “For some people, fiction is a chance to take on new identities, to see worlds through others’ eyes and return from those experiences changed.”

Mr. Pitale, a high school English teacher at ASIJ, agreed, adding that it is the imaginative nature of fiction that makes it so personal. “There are often biases attached to non-fiction texts. Fiction, being purely imaginative, takes these away and can allow a reader more space to enter and explore a story,” he said. “Fiction can help someone reimagine their own experiences through the eyes and actions of others. This can, if one is open, lead to profound introspection and changes within a reader.”