Nostalgia isn’t new. For example, fashion has been cycling back for years, with Isabel Marant’s effortless-chic boots and Herve Leger’s bandage dresses being recent examples of trend revivals. Nostalgia is also reflected in our consumer habits: digital cameras replacing phone photos, vinyl records replacing Spotify, “retro” aesthetics becoming desirable. However, the Internet’s recent hyperfixation on 2016 goes beyond another trend revival, seeming more like a collective urge to escape the weight of the present.

According to the Daily Mail, searches for “2016” on TikTok have increased by 452%, with over 55 million videos created using the app’s “2016 filter”. You have also likely seen friends and prominent pop culture icons from that era posting throwbacks to 2016, with Kylie Jenner’s post, reminiscent of her “King Kylie” era, reaching over 5 million likes on Instagram. Across all these instances, a consistent message emerges: 2026 is “about to be the new 2016”. But is this nostalgia truly wholesome, or just escapism from today’s turbulent world?

To answer that question, it’s important to understand why 2016 nostalgia hits so hard. To start, generational artists Frank Ocean and Rihanna released their top-streamed albums, Blonde and Anti—emotionally resonant albums that were zeitgeists of the year. Social media and Internet culture also felt vastly different. Platforms like Instagram, Vine, and Tumblr still seemed casual, less monetized, and less professional. Silly trends such as bottle flipping and the mannequin challenge felt harmless in a way that seems impossible to replicate today. What these memories share is a long-since-gone lack of pressure, a time when being online felt like hanging out rather than performing.

In short, culture in 2016 felt collective and light-hearted, rather than competitive and optimised. Posts weren’t made to chase virality or personal brands; they came from a genuine desire for fun and joy. Compared to today’s hyper-curated feeds and constant incentive to be strategic—more aesthetic, more productive, more viral—2016 feels, in hindsight, easier to breathe in.

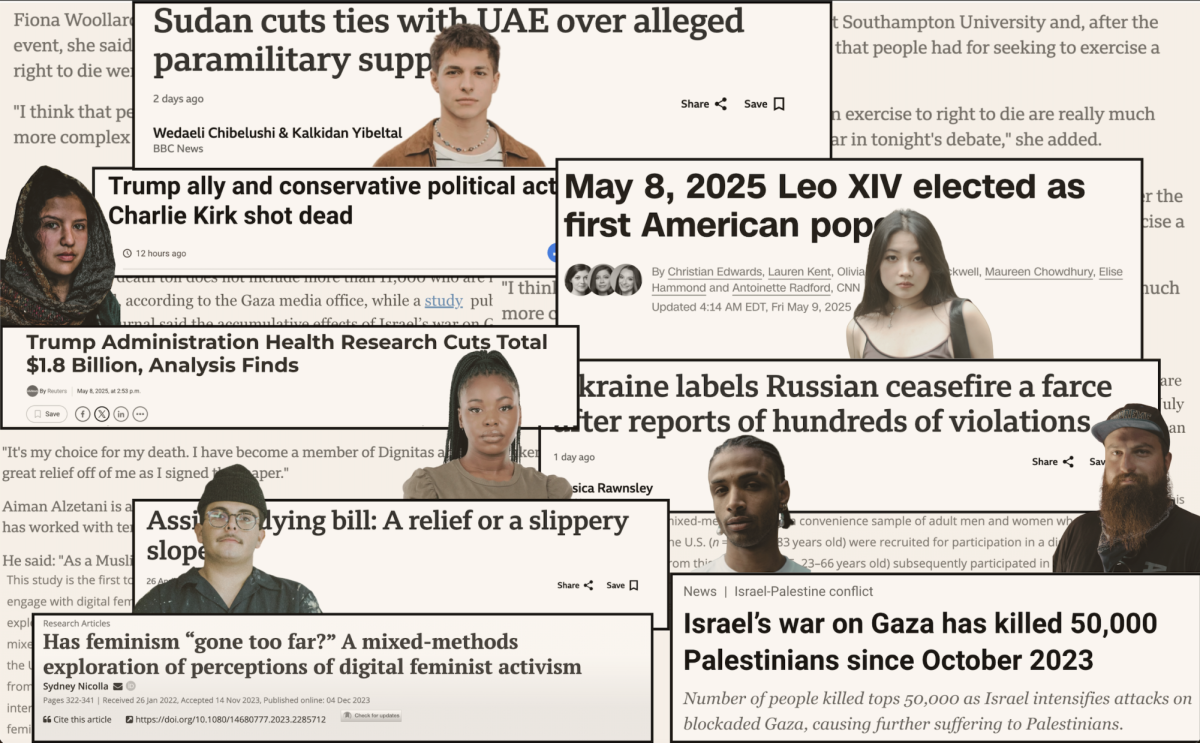

So, once again, is this nostalgia wholesome or unhealthy? On the one hand, it is making us more united through shared memories, serving as a comforting reminder that joy existed and can exist again. On the other hand, obsessively labelling 2016 as “the last great year” can turn nostalgia into avoidance. When the present feels unstable, marred by political and financial uncertainty, people feel compelled to romanticise the past rather than engage with the present. Essentially, escapism can disguise itself as nostalgia when the intent is to avoid reality.

That’s what makes this 2016 obsession revealing; it points to what people feel is missing in 2026: authenticity and connection. Gen Z has attempted to recapture this lightheartedness, particularly through the generation’s online habits. Viral “Get Ready with Me” videos feel genuine because influencers share their vulnerabilities and truthful insights into their daily lives. “Photo dumps” have surged because they reject perfect curation and allow people to upload casual and more frequent carousel posts. In this sense, 2016 represents the online experience people are now trying to recreate, not just aesthetically, but emotionally.

Although attempts to “relive 2016” can be viewed as an avoidance of the present, they’re also a way to resurface the sense of community and authenticity that made the year memorable. So maybe the goal of “2026 is the new 2016” isn’t going back, but making our present feel a little lighter to live in.