Losing Your Voice Through Grammarly

March 11, 2022

Over 30 million. That’s how many people worldwide have turned to the AI-powered writing assistant, Grammarly. In their ad online, the non-threatening generic voice boldly promises it will make your writing “clear, mistake-free, and impactful.” However, these commercials, now dangerously close to an internet sensation, advertise a software useful only to a certain extent. They can feel like a TikTok posted by The Onion when the writers have run out of punchlines.

In its essence, Grammarly splashes suggestions onto your draft to cut down any frivolous phrases or words. Pay for an upgrade, and more suggestions will appear.

If your work involves sending out emails, you’ll notice when a sender has fallen victim to Grammarly. The email will be bland and lack personality. And conspicuously so.

When using Grammarly, you are robbed of your own style —it’s the UNIQLO of AI softwares. This happens because users are nudged to accept suggestions, such as “not even a knowledgeable audience might understand this word,” or take away the “preposition at the end of the sentence.” Depending on the context, however, these mistakes may be the very rhetorical tool that defines one’s writing as their own.

Out of 30 million people who use Grammarly, a vast population are students who use it as a safety net —excluding them from further exploration of their own voice. Grammarly doesn’t inspire students to write but makes English a chore or a math equation you can cheat on using Google. Cultivating the idea that there can only be one answer to the English language from a young age could be killing aspiring authors. Why are we to think alike through Grammarly, when it’s a writer’s duty to bring new light and attitude to the table?

Perhaps one of the most harrowing trends to come out from the present era is young people’s need to fit into a cookie-cutter mold. Whether it be using repetitive jokes from TikTok, dressing in the same North Face jackets, or watching the same films, it’s a snug blanket of conformity. But always expecting to execute or receive a similar product is detrimental to students. What plastic surgery is to an insecure person, Grammarly is to a young writer. We mindlessly click on Grammarly’s suggestion box, carving out any texture and color that makes our text riveting.

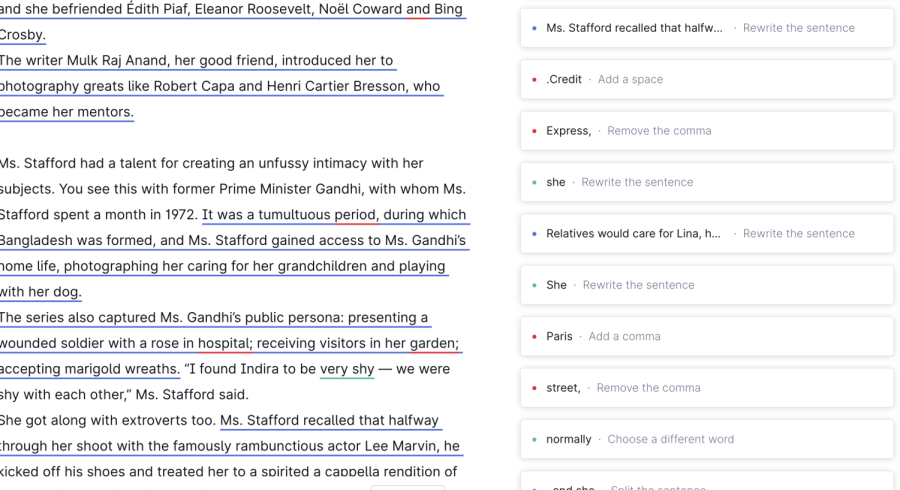

To disprove Grammarly’s spurious claims that it improves your writing, there is a short experiment anyone can conduct. Take any engrossing article written by a well-known journalist —a New York Times opinion piece, for example— and plug it into the Grammarly site. The software will bombard you with corrections antithetical to the unique style of the journalist. With this experiment in mind, it’s important to acknowledge the role of Grammarly: it is an artificial tool.

Editor’s note: The author was recognized as a runner-up in the recent New York Times review contest for this article. Congratulations, Momo!