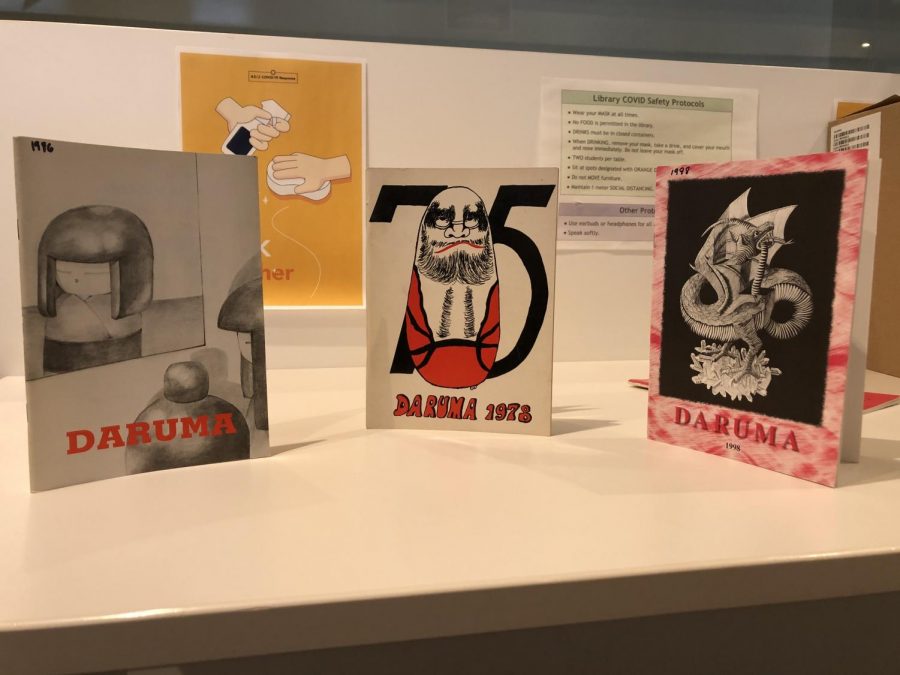

Daruma’s 50th Anniversary: Reflecting on Our Past

June 12, 2021

As the American School in Japan’s student-led literary and art magazine, Daruma, celebrates its 50th anniversary, we are naturally inclined to reflect on how, since the birth of the magazine, our world has reshaped itself.

In the past few decades, the world has seen dramatic transformations. The way we share information with others has changed drastically. The means of communication and expression for ASIJ students in the late 20th century were starkly different than they are for us. Email and social media platforms were just getting off the ground.

ASIJ alumnus and social studies teacher Bapi Ghosh points out that the internet was not available during his time as an ASIJ student from 1987 to 1990. Instead, students had no choice but to verbalize their feelings and ideas; otherwise, penmanship and journalism were opportunities for those who sought an outlet by which to express themselves. He wonders, “How did I function?”

Naturally, many students at the time turned to writing as a means of self-expression. Founded in 1971, Daruma has since published annual editions that aim to provide “insight into the perspectives of the contemporary student body.”

In celebration of Daruma’s 50th anniversary this year, the magazine team had planned to scan past editions to make them available online. Certainly, in the process, great writing and art were discovered and shared; however, the team was also surprised to find pieces that would be considered inappropriate in the current social climate. These pieces, starting in the 1970s and most recently until 2001, include the n-word, fat-shaming, call-out of teachers by name, and references to personal family situations.

For instance, in one poem titled “Hey! Ni***r!”, the author writes of a “black man working janitor” who “smokes too much to sing spirituals so he has to settle for some jive Kunta Kinte stuff.” Another piece, simply titled “Mr. _____ ASIJ’s Male Chauvinist,” discusses a specific, real teacher’s misogynistic behavior toward female students in the science classroom.

In 1989, a fictional piece titled “The Fat Girl” was published; the piece describes a student named Lanna as being “conscious of her enormous thighs pressed next to each other.” At the end of the story, the author describes Lanna shooting her classmate in an act of revenge in grotesque detail.

Other pieces include highly personal stories of cheating parents, religious trauma, and divided families. These students may have been comfortable sharing segments of their lives in a school magazine and with people they knew: classmates and teachers. However, would the author of these personal stories be at ease with sharing the pieces with strangers on the internet?

Reading over such stories, the Daruma team was now faced with a predicament.

One possibility was that the articles could be published for members of the ASIJ community as a way to share a concrete, significant piece of the school’s history. Perhaps the authors of the pieces should take responsibility and ownership for their own writing.

On the other hand, if Daruma published the pieces online, names included, the authors—some now in their 50s—would potentially face backlash for choices made in their teenage years. Those authors had never given consent to have their pieces viewed by people around the world; at the time of publishing, many of the authors would have had no idea that a tool as powerful as the internet would come to existence.

Max Duncan, the faculty advisor for Daruma, wondered, “How fair is it for us to judge them?” According to Mr. Duncan, the real conflict that the Daruma Team faced was walking the fine line between “accurately preserving history” and unfairly holding these past students accountable for pieces they never expected to leave the ASIJ community. He asked, “What responsibility do we hold as publishers?”

Because the magazine exists as an encapsulation or representation of the student body at the time of its publishing, Mr. Duncan suggests that we approach these pieces with the intent to understand and learn the context in which they were written, rather than to “judge or expose the original writers.”

Thus, the importance of not burying the shameful parts of history remains a fundamental facet of this conversation. We cannot simply pretend that these issues are not a part of ASIJ’s history and a part of history in general. Karen Noll, the former advisor of Daruma and current librarian, noted, “It reveals the great beauty and great dilemma of history.” Certainly, our focus should be placed on how we can learn from the mistakes of our past and move forward as a more educated and informed community.

Being aware of the history of ASIJ is especially significant, as in the spirit of the times the school community has taken appreciable steps towards becoming more socially conscious. Inspired by the anti-racism Black Lives Matter protests occurring globally in 2020, more than 300 high school students at ASIJ attended a student-led panel discussion titled “I Can’t Breathe – A Discussion About How Racism is Choking America.” At the same time, alumni of ASIJ wrote a letter addressing the failures of the school in preparing students for the complexities of the world after leaving the insulated bubble of ASIJ.

In the past year, the ASIJ community has continued to provide various educational opportunities around anti-racism for both the faculty and students. Specifically, the school has made significant strides towards a more anti-racist environment by implementing a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) statement into Board policy with the hopes of creating a lasting framework for ASIJ’s institutional commitment to DEI in their already-existing systems, curricula, school culture, and so forth.

As members of the ASIJ community invest time and resources into learning more about these issues, we must also ask ourselves: How can we look inward at the roles that we play in exacerbating the very faults in the systems that we are so wrapped up in? How do we ensure that the community does not allow our privileges to cloud our ability to recognize the history of ignorance within our own school?

As illustrated by its various recent actions, ASIJ in its current state clearly promotes a set of values, including anti-racism. Yet, many members of our community are unaware that this was not always the case at ASIJ. The Daruma pieces are primary sources that provide insight into the nature of the school community in the late 20th century. As Ina Aram, student leader of Daruma, states, “the magazine holds moments in history.”

As a primarily caucasian school at the time, racial issues and social issues, in general, were rarely a topic of discussion among the ASIJ student body. Even in the early 2000s, a photo exhibition of non-traditional families (with two moms or two dads) was blocked from being shown in the main lobby by parents hoping to shield their young children from the supposedly abnormal family model. The exhibition was instead moved to the second-floor hallway as a compromise; the project still received backlash from some high school students.

When the Daruma pieces were originally published, the parts that we now consider blatantly inappropriate were not discussed by the community in a negative light. Ms. Noll clarified that the purpose of Daruma has never been to investigate or expose concerns at ASIJ. Therefore, the pieces published by the magazine would not have been intended as a call to action. Ms. Noll, like many of us, is perplexed by some of the material, for instance “the piece about the male chauvinist [teacher] upset me but I still don’t know what the purpose of it was.” If the motive was not to uncover issues that had been swept under the rug, “was it humor?”

In considering what words and actions we now see as problematic, one thought-provoking question comes to mind: How will our actions today be perceived fifty or so years down the line? Will our well-intentioned actions and words be understood as insensitive or even offensive in the future? With social media documenting every moment of our lives, everything is made permanent and we must be particularly vigilant about what we put out into the world. But as Ms. Noll commented, the reality is that “you cannot be fully aware of yourself at the moment.”

While the adage of thinking before we speak continues to be a wise piece of advice, being overly conscious of our every move can be detrimental as well. It is virtually impossible to predict how our actions today will be received in the future. Just as these past Daruma writers expressed their ideas based on the social context of their time, we, too, must do the same.

Daruma is one of the many critical platforms for students to express and share their feelings, ideas, and beliefs. History is a powerful precedent; our school has completely transformed since Daruma was first published fifty years ago, and will continue to do so. As Mr. Ghosh noted, “We have to evolve. We have to continually change.”